| Lukang A few photos from our trips of January, 2006 and July, 2006 back to Teaching English in Taiwan |

| Some

background....the heyday of Lukang Lukang: Commerce and Community in a Chinese City Don Deglopper 1995 Don Deglopper began working in Lukang in 1967 and 1968 as

an anthropologist, and has continued his research there over the years.

Here is an excerpt, edited to simplify the English, that I used in a

class on Taiwan a few years ago. During the nineteenth century, Lukang was a city of wholesalers and middlemen, with many large firms in the trade in rice, cloth, sugar, timber, and pottery. Oxcarts and gangs of workers moved through its narrow streets, carrying the two annual rice harvests from inland. Hundreds of workers loaded and unloaded the bamboo rafts and small boats that carried cargo to the larger ships in the harbor channel. Thousands of men carried bales of rice across the Changhua Plain on shoulder poles, while some walked down from the mountains carrying goods from the forests. No one knows how this army of workers earned their living during the winter when Lukang port shut down. Lukang's merchants lived in big houses, the bricks and tiles of which had been imported from Fukien. The shoes they wore, the dishes they ate from, the paper they wrote their accounts on, and even the ancestor tablets they worshipped were all made by craftsmen in Fukien and shipped across the Straits. Lukang had official buildings, granaries, warehouses, temples, and academies, and was the site of magnificent annual festivals and displays of wealth. But it produced practically nothing for itself, and depended on the trade that exchanged the rice and agricultural produce of central Taiwan for the cloth and manufactured goods of southern Fukien. By the second half of the nineteenth century Lukang's total share of Taiwan's trade and its relative importance in the island's economy had begun to decline. This may have been the result of a decline in the volume of trade at the city, but more likely was caused by the economic growth of the northern part of the island and by changes in Fukien's rice trade. The years after 1875 saw the development of the tea industry in northern Taiwan. Foreign firms, mostly British, set up businesses in Taipei, and the Japanese began exporting manufactured goods like textiles and matches to Taiwan. Taipei grew rapidly, and labor in the northern third of the island was so scarce that tea-pickers had to be brought in from Fukien each year. Lukang's primary export had always been rice, but the rice trade appears to have fallen by the end of the nineteenth century. Taiwan's population grew and more rice was eaten by the city dwellers, tea-pickers, and coal miners of the north. Fukien did not have any problems, for it was able to import rice from Southeast Asia at a lower price. Since no steamship, even of moderate size, could get anywhere near Lukang or safely enter the shallow harbor, the sailing ships sailing in and out of Lukang were not directly threatened. But Lukang's trade with the mainland was threatened indirectly when large steamships were able to bring rice from Southeast Asia more cheaply than it could be shipped over from Taiwan in small ships. And any improvement of land transport, even in Fukien, directly threatened Lukang. The city functioned as a port, in spite of silt, tidal mud flats, the necessity of employing gangs of workers to load everything into small ships by hand, and the danger of storms and shoals in the Straits, only because there was no better way to move things into and out of the Changhua Plain. The only available figures on Lukang's trade and population are those published by the Japanese colonial government...the only figure I have found is a statement quoted by Wang Shih-ch'ing, probably from an early Japanese source, that in the early years of the Hsien Feng period (1851-1862), just before the long decline began, over 3,500 ships came to Lukang each year. In 1896 the Japanese customs authorities counted 1,051 ships coming to Lukang, although that number declined to 515 in 1897 and to 229 in 1900. By the end of the nineteenth century the trading system linking central Taiwan and the China coast was already declining as the rice trade gradually disappeared and Japanese imports began to replace Fukienese cloth. Under the Japanese the commerce between Taiwan and Fukien shrank further and the trade of Lukang, by then only a minor port, almost died. The Japanese built roads and the railroad, and so made it possible to move goods into and out of the Changhua Plain more cheaply than they could be shipped through Lukang's silt-choked harbor. The colonial government developed Keelung and Kaohsiung (then called Takao) as modern, deepwater ports… Lukang was left with a commercial population far too large to support itself by selling things to local villagers. Some of its wealthy merchants looked for new investments and bought farm land. They favored the highly productive land around the town of Yuanlin, twenty kilometers to the southeast. Some simply became landlords and lived on their rents. But others, recognizing that they could not defeat the modern transport technology that had destroyed the city's commerce, chose to join it and moved to Taipei or the booming port of Kaohsiung. The first decade of the twentieth century saw massive emigration from Lukang. By the end of the nineteenth century some Lukang businessmen had already established themselves in the thriving commercial quarter of Taipei, a city that was rising as Lukang fell. They were soon joined by crowds of their fellow townsmen. Lukang, which had been settled by emigrants from southern Fukien, now produced its own emigrants. In the Taiwan of the early Japanese period, an agricultural society undergoing rapid economic development and urban growth, the Lukang emigrants with their greater commercial expertise and literacy had an advantage over ordinary Taiwanese from the countryside. Furthermore, they did not go to Taipei, Kaohsiung, or Puli as individuals. They went with introductions to other Lukang men who had already established themselves, and they joined the Lukang associations that existed in all Taiwan's major cities. (A Lukang Guild was founded in Taipei in the late1800s, before the Japanese conquest, and was one of the five great guilds of Taipei.) |

Lukang is in the flattest part of the west coast plain, right on the ocean. As the city has declined in economic importance, its retailers have moved into marketing tradition, selling religious furniture and implements, and its own history, done in kitsch for the tourists. Here we approach Lukang from the east down Rte 142. Note how flat and straight the roads are. |

Another view, further down. |

The first major site for most tourists is a prominent local temple, which dates from the first two decades of the 19th century, when the town was just rising to economic prominence. |

The temple today is a pleasant parkland of trees and grassy areas, and well preserved, if lifeless, buildings. |

|

|

|

|

|

You can make an annual payment to the temple, get your name inscribed herein, and the temple will include you in its prayers. |

|

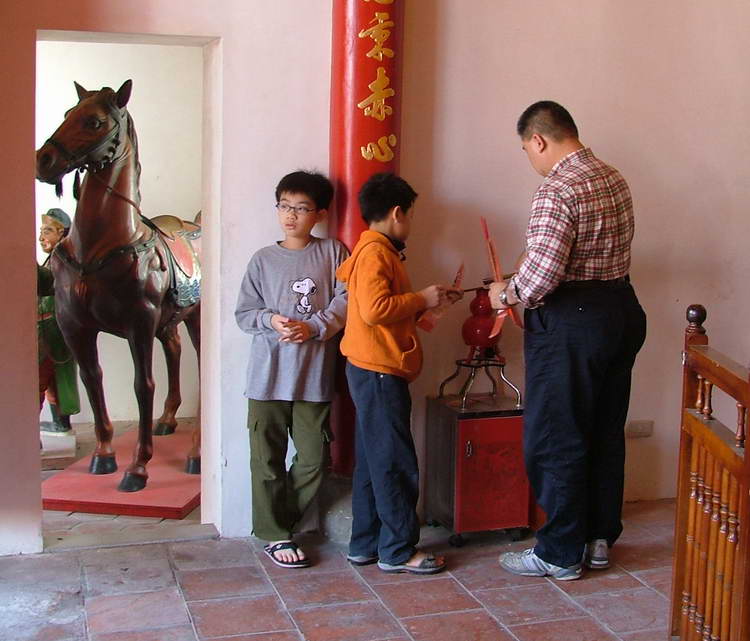

Here a father and his sons light tapers of incense for devotional offerings. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Some of the areas still have older wooden fixtures. The Chinese generally make no attempt to preserve the authenticity of their objects by restoring their original condition. Rather, over time, they tend to completely reconstruct. |

|

|

|

A man selling traditional ice cream. |

Lunch. A stuff-yourself-til-sick lunch like this cost NT$375 ($US11) for four. |

After lunch we visited the Buddhist Hall owned by my wife's family. The caretaker, whom we have known for 15 years, was sitting outside enjoying the beautiful weather. |

A view of the Buddhist Hall from the outside. |

There has been a Buddhist temple on this site, and in my wife's family, for a couple of hundred years. The original hall has long since been razed and this upgraded one built. |

A large kitchen can accomodate feasts and banquets as necessary. |

|

|

Some original parts of the previous temple still exist. Here are some paintings. |

|

The family altar to my wife's deceased ancestors. |

It is traditional in almost every temple to have a large incense burner by the door. Temple-goers are supposed to leave tapers of incense burning there. |

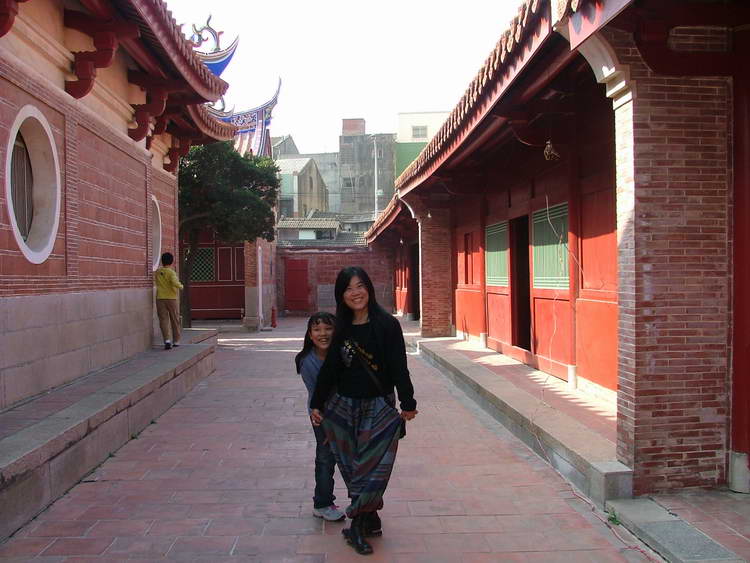

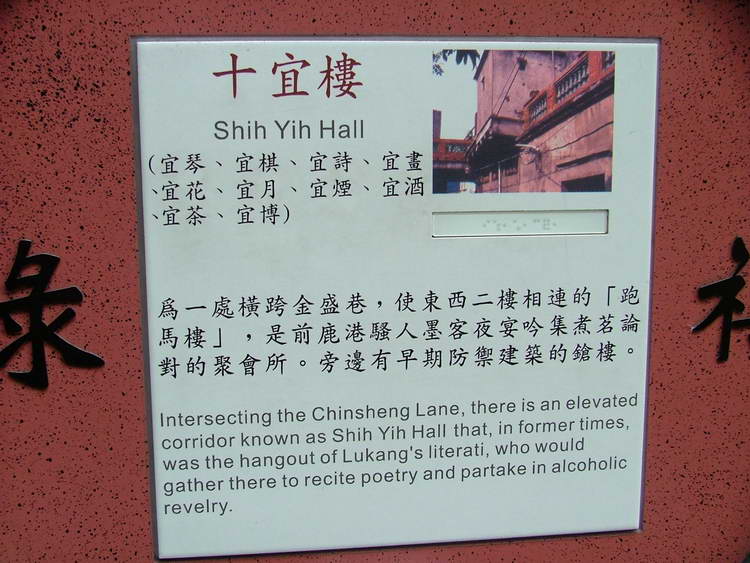

One of the attractions of Lukang is its collection of old buildings. One of the narrow streets has been preserved and restored to give it a 19th century feel, and is a frequent site of television shows and tourist photography. It is lined with historic homes and temples. The lane is so narrow that locals nicknamed it "mo ru" (rub your breast) street, since you can't walk by someone without brushing up against them. |

The street has been paved with brick. |

It is also a popular site for couples to come photograph each other. Taiwanese recreation is generally very passive, involving the actions of (1) going to a site to take photos of each other and (2) eating. People from countries for whom "recreation" means activities often find Taiwanese outings maddeningly dull. |

|

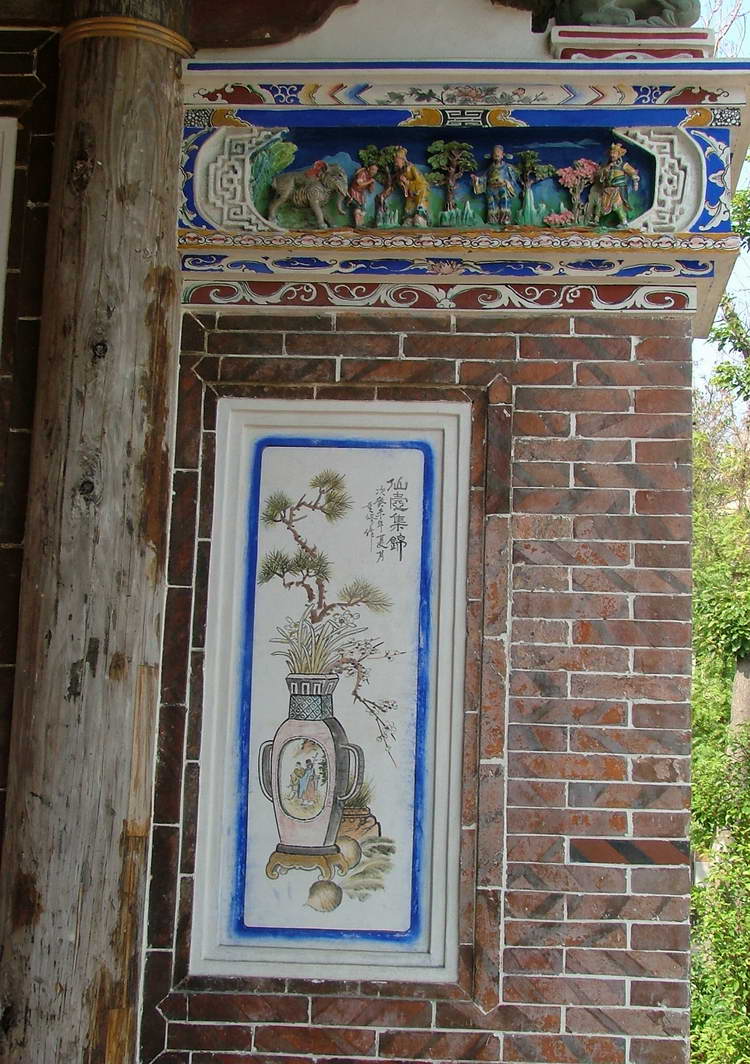

A detail of a temple along the way. |

|

Tourist trekking through the paths. |

The lane debouches into the local market. |

|

Packing pork intestines into a plastic bag. |

|

Like all Taiwanese cities, Lukang's sidewalks are taken up by vendors and motorcycles. |

|

Inside a temple. |

Here we enter one of the most famous bakeries in Taiwan. No trip to Lukang is complete without a visit here to pick up a famous local specialty. As my wife noted, you can tell the tourists: they all carry the distinctive bags of this bakery. |

|

The most famous local specialty, 'cows tongue'-- flat sweetbreads stuffed with a sugary paste and sprinkled with sesame seeds. Yum. |

|

"Made with black sugar!" the woman assured me. "Good for your health!" |

A vendor sells noodles, betel nut, and whatever else she can. |

|

A 19th century temple tucked into a back alley. |

|

|

After walking around Lukang we decided to visit the Lukang Folk Arts Museum, housed in a Japanese period building. As this site notes: A good place to start your tour

of the town is the Lukang Folk Arts

Museum (鹿港民俗文物館), just a short walk from the bus station. This striking

Japanese colonial structure, built in 1920, was once the home of the

Koo family, among Taiwan's largest landholders at the time.

Koo Chen-fu (辜振甫), son of the builder and chairman of the Taiwan Cement Company, donated the building and much of its contents for use as a museum. Its doors were opened to the public in 1973. On the whole, I recommend the Museum, but with certain

reservations that will become clear. The price is $130 for an adult,

$70 for a kid. |

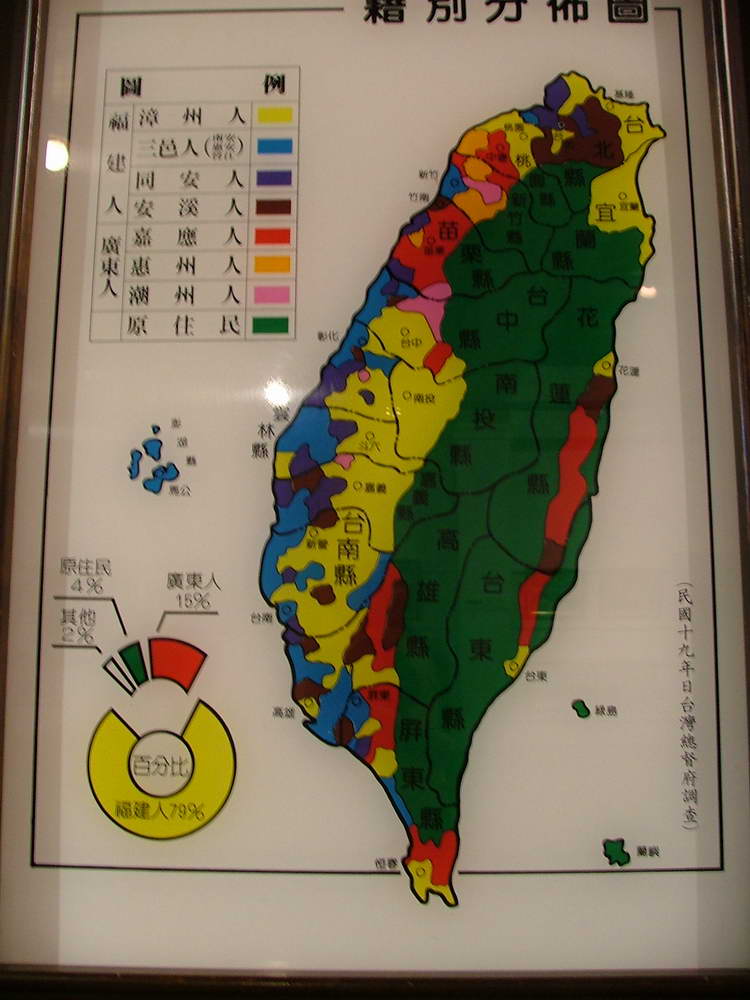

Photography is not allowed in the museum, so don't tell anyone I took these pictures. Here is an out-of-focus shot of a map of the origins of the Taiwanese. The museum has a relentless political slant in that it "explains" the origin of the artifacts within by reference to their mainland ancestors, without much discussion of what happened to them over time in Taiwan. Sad. |

A diorama of Lukang "200 years ago" (Chinese) or "c. 1700" (English). Unfortunately in several places in the museum the English and Chinese do not agree. |

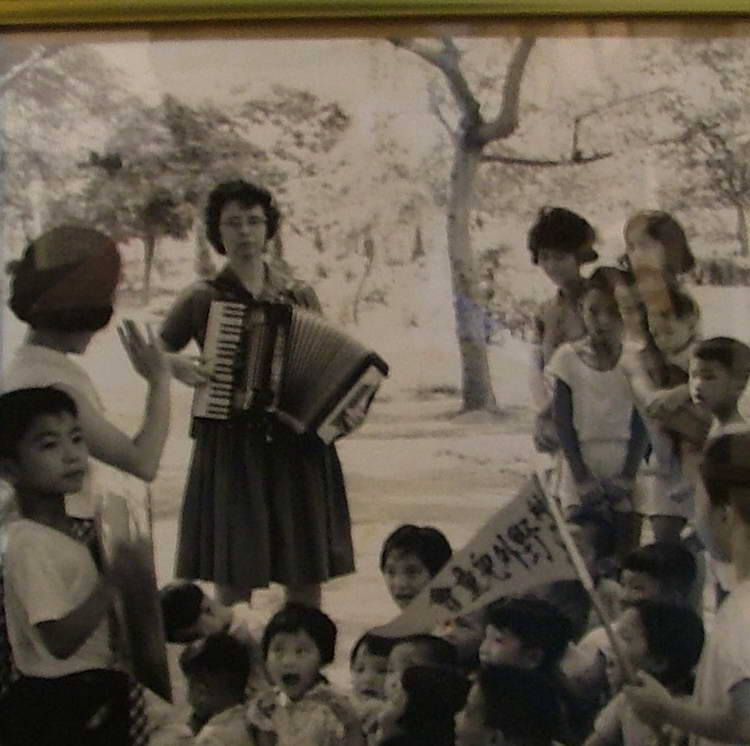

This was my favorite object in the museum. A series of B&W photographs, probably originating with some missionary, and dating from the 1950s, provided this classic of a white female playing the accordion for a group of Taiwanese kids, not one of whom is watching. I especially loved the sour expression on her face. Here is a case of cultural imperialism as a parody of itself. |

The grounds of the museum are gorgeous. |

The local costumes area. |

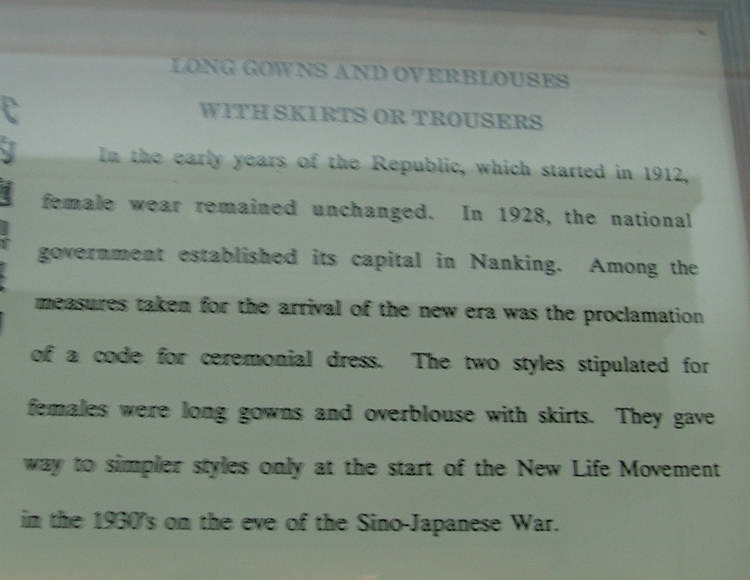

Read this carefully. Ostensibly it discusses fashions from the Republican period. Note that it does so without ever mentioning the fact that the Japanese owned Taiwan in this period. Nowhere in this exhibit will you find the slightest hint that locals wore kimonos and other Japanese clothing, along with their traditional Chinese wear, and that whatever fashion changes occurred on the mainland, their effect on Taiwan was limited and/or nonexistent. The museum staff has made an entire swath of Taiwan's history disappear from the exhibit, and substituted an idealized version of a Sinicized and Republican Taiwan. While the black & white photos above exhibit one kind of cultural imperialism, this sign exhibits another. |

|

Figurines made from flour, a local folk art. |

Sebastian practices with a local toy. The museum has a small collection children can play with. |

|

|

If you need help, the old guard there will be glad to lend a hand. Here the kids try to walk on stilts. |

After visiting the museum we walked over to the Tien Hou Gong, the most famous temple in Lukang, and one of the best-known on the island. Along the way I grabbed some phoots of the many small temples that dot the town. |

Carvings and other handrcrafts, as well as tourist junk, are a big item in Lukang. |

A Chinese medicine store. |

A lantern shop. |

The main drag of the city is lined with beautiful lanterns. |

A lantern seller. |

An incense seller. |

A shop selling traditional family altars for individual homes. |

Stopping for tea. |

|

The approach to the temple is a crowded market area. |

If it weren't for sausages, my son would starve to death. Sadly, only one kind of sausage is widely available. |

|

|

A vendor checks buns steaming on their way to my stomach. |

A traditional local snack, mwa ji, made with sticky rice flour and sweetened bean paste fillings. Yum. |

Various types of mwa ji for sale. |

|

The area around the Tien Hou Gong is also filled with restaurants catering to tourists. |

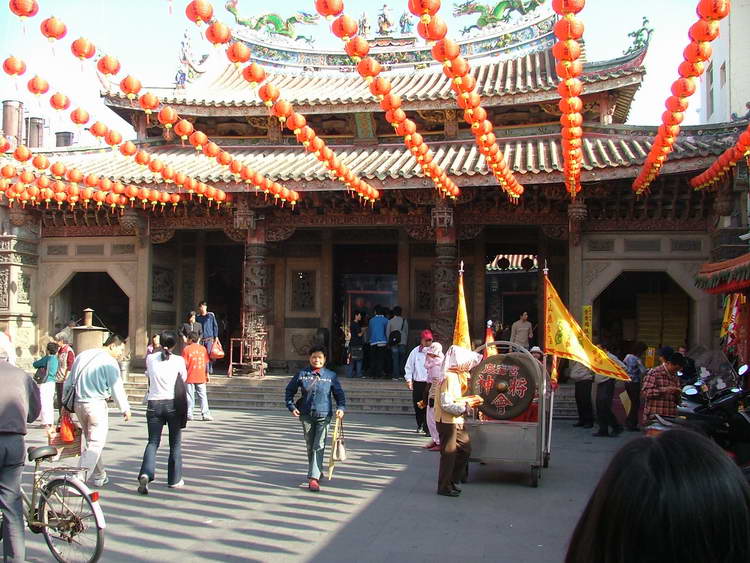

The Tien Hou Gong. |

Vendors line the space in front of the temple. |

Taking a break from the hard work of selling. |

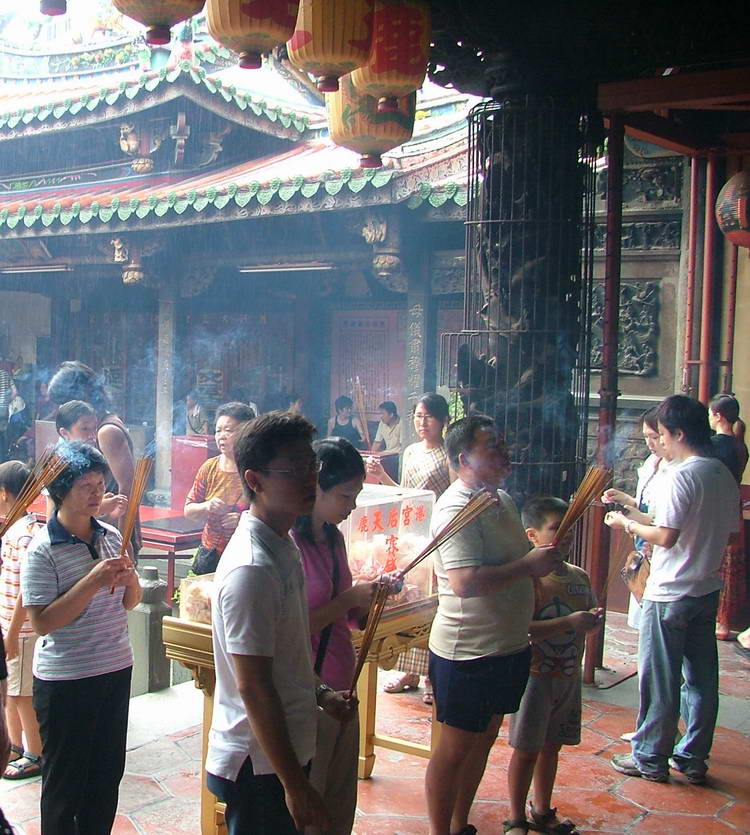

Inside the temple. One of the things I like about Chinese temples are their warm, human feel. Rather than the remote, soaring distances and inhuman, tomb-like silence of the Catholic churches I grew up in, popular Chinese temples are alive with noise and energy, places where humans go about all sorts of human activities, from running and playing, to selling and praying. |

|

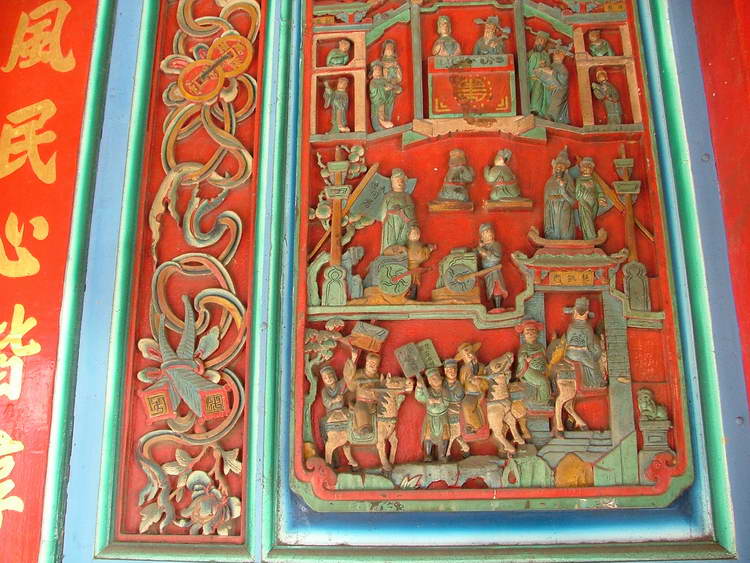

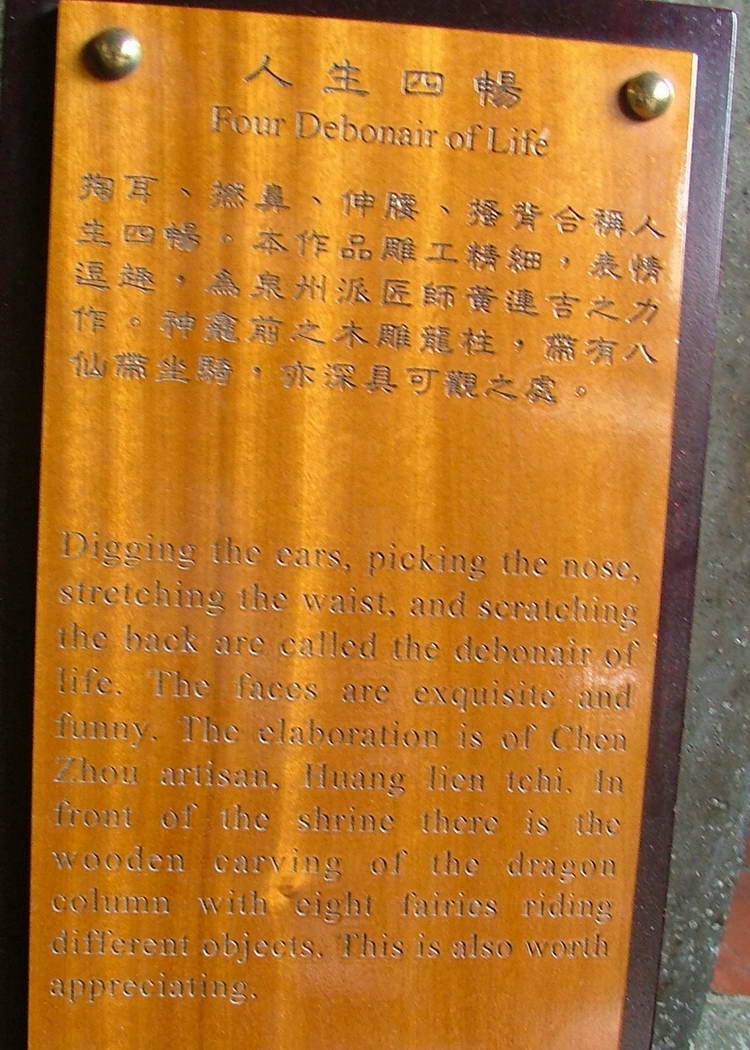

A sign describing one of the sights inside the temple. |

|

|

|

|

|

Good-bye, Lukang! |